“Daisy Jones and the Six” Broke My Brain

Trying to unravel reality and artifice in the Amazon series and accompanying album

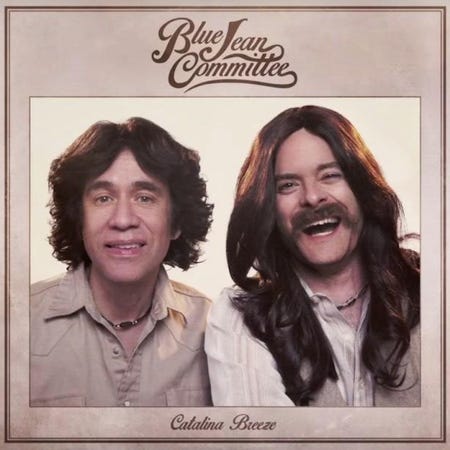

There’s an episode of documentary parody series “Documentary Now,” by Fred Armisen and Bill Hader that takes aim at the ubiquitous genre of music documentaries, which anyone who grew up on VH1 Behind the Music will instantly recognize. In two parts, overwrought talking heads (real musicians) discuss the absurd rise of a fictional ‘70s band called The Blue Jean Committee, their melodramatic downfall, and where they are now. The band is formed by hardworking, honest Gene Allen (Armisen) and his high school bully, Clark Honus (Hader). Their hit album, “Catalina Breeze,” is composed of songs that basically sound like the Beach Boys, but stupid. The barbs at various bands of the era include the fact that Blue Jean Committee (BJC for short) is a California-themed band that isn’t even from California, like the Beach Boys, and that the band’s two members are basically one guy who does everything and the other guy who “just sings really high,” an obvious jab at Simon & Garfunkel. I couldn’t stop laughing.

But while the tale of the Blue Jean Committee is an obvious spoof, the book and new Amazon series “Daisy Jones and the Six” it's based on takes the format seriously. Both are structured as documentary interviews conducted with band members and people close to them, with the action all occurring decades before in flashback. While reading the book, I found this structure rather cringe. I felt like a furtive teenager secretly reading fanfiction in the middle of the night, this time Fleetwood Mac-themed rather than Harry Potter. While it was still a little corny, the subject and format was much better suited to the screen, where you can actually hear the music rather than reading pretend lyrics on a page. Though watching requires a certain suspension of disbelief, beyond the incredibly unconvincing aging makeup on the band members being interviewed years later, Blue Jeans Committee this is not.

But the show presented for me a curious paradox of real and fake, or authenticity and artifice. As many reviews have noted, the show is clearly a promotable Product, and its slickness is in some ways at odds with the gritty aesthetic the era the show is emulating. As a review in Autostraddle poked, this show is for people who buy Fleetwood Mac shirts at Urban Outfitters. The marketing for the series includes an album recorded by the titular actors-cum-bandmates, a Free People clothing line based on Daisy’s outfits in the show, and even a themed scented candle collection. There is something too neat and clean about the packaging of this show, which is produced by Reese Witherspoon's very neat and clean production company Hello Sunshine. But despite the glitzy packaging, there’s no denying it’s an ambitious project, and it’s grounded by credible emotional and musical performances by the actors, especially Keough.

Even though the whole conceit of the show is an artifice– a fake documentary of a fake band with real music– the show’s development team made certain other choices to make the series seem more authentic. The album is pretty decent; some of the songs are veritable earworms, and Keough and Sam Claflin, who plays frontman Billy Dunne, have good voices. The concert scenes were the best of the show. Oddly, neither Keough (Elvis Presley’s granddaughter) nor Claflin had sung before, but I guess they had enough potential and vocal training to transform them into relatively believable ‘70s superstars. I found this both impressive and a bit disconcerting. I thought being a singer was about raw talent, having that special “it” factor, but can anyone in fact simply be molded into a facsimile of that special something? But if you look up videos of Fleetwood Mac performing in the ‘70s, you can tell that Keough, or Keough-as-Daisy, depending on how you want to look at it, is no Stevie Nicks. She doesn’t have Nicks’ famously gravelly voice, the passion, or the range. But she and Claflin did well enough that I didn’t bat an eye at the idea that either of them could be professional or famous singers in the ‘70s.

Rather than having the actors lip sync or pretend to play their instruments while real musicians performed the overlaid tracks, the actors went through months of intensive “band camp” training so they could learn to act like a real band. (The songs were mostly written by producer Blake Mills as well as modern-day songwriters like Marcus Mumford and Phoebe Bridgers. A pre-Daisy song by The Six is even penned by Jackson Browne, who was like, actually around in the ‘70s.) The result is something like “That Thing You Do!” the 1996 movie about a one-hit-wonder band in the early 1960s called the Wonders, which featured perhaps the best fake pop song I’ve ever heard, by brilliant songwriter and Fountains of Wayne frontman, Adam Schlesinger (who sadly died early in Covid). I liked most of the songs on the Daisy Jones album, and a few of them I was quite fond of, and got stuck in my head for several days, while others were too simplistic or plot-devicey. But “films with fictional hit music must achieve a… improbable feat: creating songs that are not only good, but believable as something you would absorb from the cultural atmosphere,” the Guardian conceded.

Some reviewers have noted that the lyrics lack the complex symbolism and imagery of the real Fleetwood Mac songs penned by Stevie Nicks and ex-lover/frenemy Lindsey Buckingham Daisy and Billy are clearly based on. At one point in the series Billy criticizes Daisy’s lyrics for being too poetic and too metaphorical, and urges her to be more direct. Her lyrics change overnight from turns of phrase like “stumbled on sublime” to “driving down the PCH highway with a typical wonderful view, go ahead and regret me but I’m beating you to it, dude.” Leaving aside the glaring repetition of “the Pacific Coast Highway Highway,” it struck me as odd that the script would use this particular note to show how Billy helped Daisy’s songwriting, and vice versa.

“You’ll regret me and I’ll regret you” from “Regret Me” clearly has nothing on “You'll never get away from the sound of the woman that loves you” from “Silver Springs,” the song that inspired Jenkins Reid to write Daisy Jones and the Six after watching Fleetwood’s intense performance of the song.

TikToks of that performance, and so many cast behind-the-scenes videos and interviews that it had to be part of their contract, dominated my FYP to a degree I had never experienced before in the days after I finished the show. And watching real Fleetwood Mac footage drove home the conclusion that something was absent from the Amazon show. Some kind of grittiness, or imperfection, or individuation.

The closest approximation I can think of to this kind of project– other than the Blue Jean Committee, who also have a fake/real Spotify album that Pitchfork described as “ultimately an impressive, if perhaps not entirely necessary, follow-through on a joke,” would perhaps be a Broadway musical. Many of the songs do in fact sound a bit like Broadway versions of Fleetwood Mac songs– earnest, theatrical, lacking texture. Pitchfork reviewed the Daisy Jones album, “Aurora,” too, saying, “More often than not, it ends up sounding like a Broadway tribute.” Yet the author slaps it with a 6.6 out of 10, which is honestly respectable for Pitchfork. And isn’t it kind of strange that a Pitchfork review would even exist of an essentially fictional album in the first place? At least Broadway albums have the word “soundtrack” on them. But “soundtrack” here wouldn’t be accurate, because there is a soundtrack to the show, and it’s filled with real songs from the ‘70s, from Carole King to actual Fleetwood Mac, a real band that exists– Stevie Nicks is still very much alive and touring, and something tells me she is way above even considering a throwaway guilty pleasure show like this. It’s like imagining Queen Elizabeth watching “The Crown.”

After a certain point of thinking about it, the whole concept started to break my brain. So… Daisy Jones and the Six are a fictional band with real music not written by but performed by actors, meant to approximate a real band, who are playing their characters while singing the real songs. And even if the songs are real, they were very much not written in the actual ‘70s, which was, somehow, half a century ago. If that’s not too much, add the fact that they are considering going on tour. How would this even work? Would Riley Keough and Sam Claflin still be playing Daisy and Billy onstage, or would they just be themselves? Then again, many musicians have onstage personas, from Ziggy Stardust to Sasha Fierce, or even pseudonyms. But those are, um, real musicians. But aren’t Keough and Claflin now, too? Lots of artists don’t write their own music.

All of this brings up some more complicated ideas about artifice and authenticity in art. After all, all acting is performance, set in an alternate reality about usually fictional characters. In a traditional sense, good acting, we’re told, is realistic and believable – it seems real. Bad acting, on the other hand, is hammy and obvious – it feels fake. That’s why “Succession” is so good; you truly believe Jeremy Strong’s embodiment of Kendall Roy; as a viewer you can’t tell where the actor ends and the character begins. Biopics are considered quality if the actor “embodies” the spirit of the person they are playing, if they look like them, if their manner of speaking is similar, if we identify with their struggle. On the stage, the distance between actor and scene is greater, which perhaps explains the Broadway comparison in “Daisy Jones.”

Sometimes as a viewer of “Daisy Jones” you can feel that fissure. Those are the moments where you can’t quite suspend disbelief quite enough to buy into what’s being sold– that Billy and Daisy are that connected, that the band could get that famous that quickly, the excitement of finding success and the devastation of things falling apart. The result can feel oddly bloodless. The writing of the show could have something to do with this, or the casting of three former models as the female leads of the show, who are all fine actors but make the band less believable. Some reviews have reduced the character of Daisy to a “manic pixie dream girl,” and while I don’t agree with this, you can fit most of the characters, who aren’t developed enough necessarily to be individuated, into archetypes. It is, after all, based on rock ‘n’ roll cliche.

Despite all this, I got really, really into the show, and couldn’t help but binge it in just two days. That says something about it, I think, even if it isn’t, as a friend described, “the deepest thing on earth.” At the end of the day, Alexandra Molotkow writes, “the show “never had to be good, just marketable.” It worked on me, anyway.

Editor’s Note: First, apologies for the long hiatus between posts. I just moved across the country and have a very different job and life than before, and am trying to determine the future of this newsletter. Also, I know that the '1970s are neither millennial or Gen Z, but the characters in the show are in their ‘20s and most of the series’ fans are, too. Also, I couldn’t figure out where else to pitch it.